This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU:DIY Guides Streaming Business Library

Music Streaming Explained

By Chris Cooke | Last Updated: July 2022

Here we go – get to grips with the basics of music streaming – and how the streaming business works – in five easy steps.

You can also download the slides that accompany the lecture version of this guide and buy the ‘Dissecting The Digital Dollar’ book published by CMU and the UK’s Music Managers Forum. Plus check out more music streaming resources available elsewhere in the CMU library.

#01: There are many different kinds of digital music services – different kinds of services operate different models.

There are obviously many different digital platforms that use music in one way or another. We can organise these platforms into a number of categories.

Each category – ie each kind of digital music service – operates a different business model and will therefore be licensed in a different way by the music industry. Key categories include…

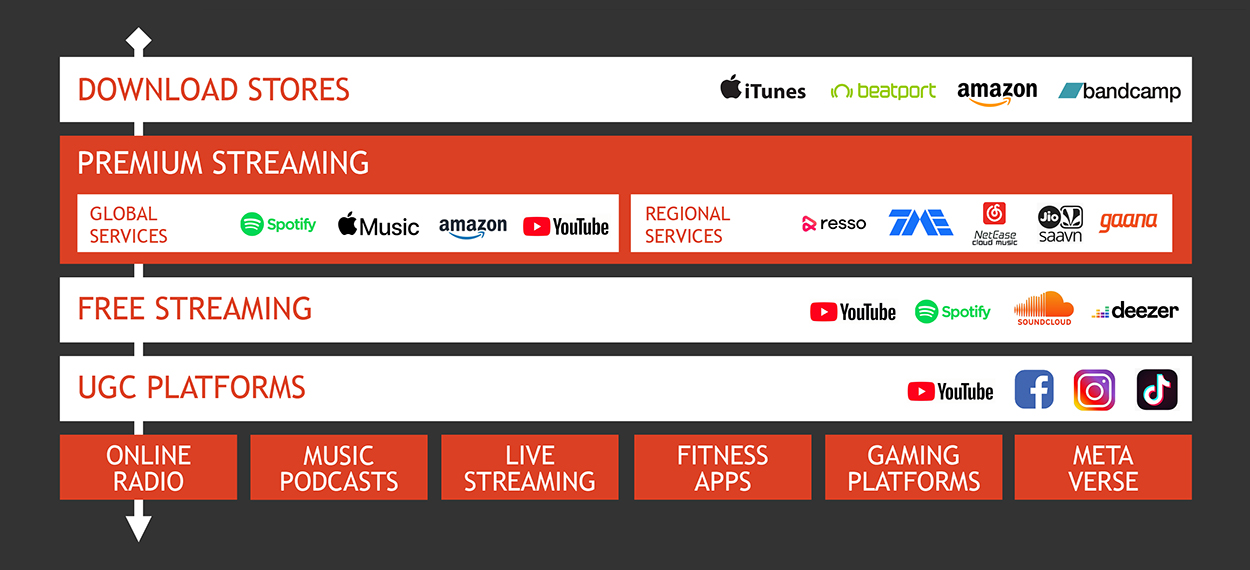

Download stores like the iTunes Store, Beatport and Bandcamp which sell digital music files – and were the most popular kind of digital music service in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

Premium streaming services where users pay a subscription fee to access a large catalogue of music on-demand. Some of these operate in countries all over the world – like Spotify, Apple Music and Deezer – while others are focused on certain specific countries, like the Tencent and NetEase services in China, and the JioSaavn and Gaana services in India.

Free streaming services paid for by advertising where users can access a large catalogue of music for free, but with limited functionality and regular ads. Most free streaming services are actually free tiers offered by premium streaming services.

User-generated content platforms where music is used by creators in their videos. Most of these platforms now have in-built audio clip libraries that allow users to easily include backing music in their content.

In addition to these four key catalogues of digital music services you also have online radio stations, music podcasts and live concert streaming services, plus fitness apps, gaming platforms and metaverses that make use of music.

Currently premium streaming services generate by far the most money for the record industry. These services all operate on basically the same model, which is the model we will describe in more detail in this guide.

#02: Digital services license recordings and songs separately from music industry companies and organisations.

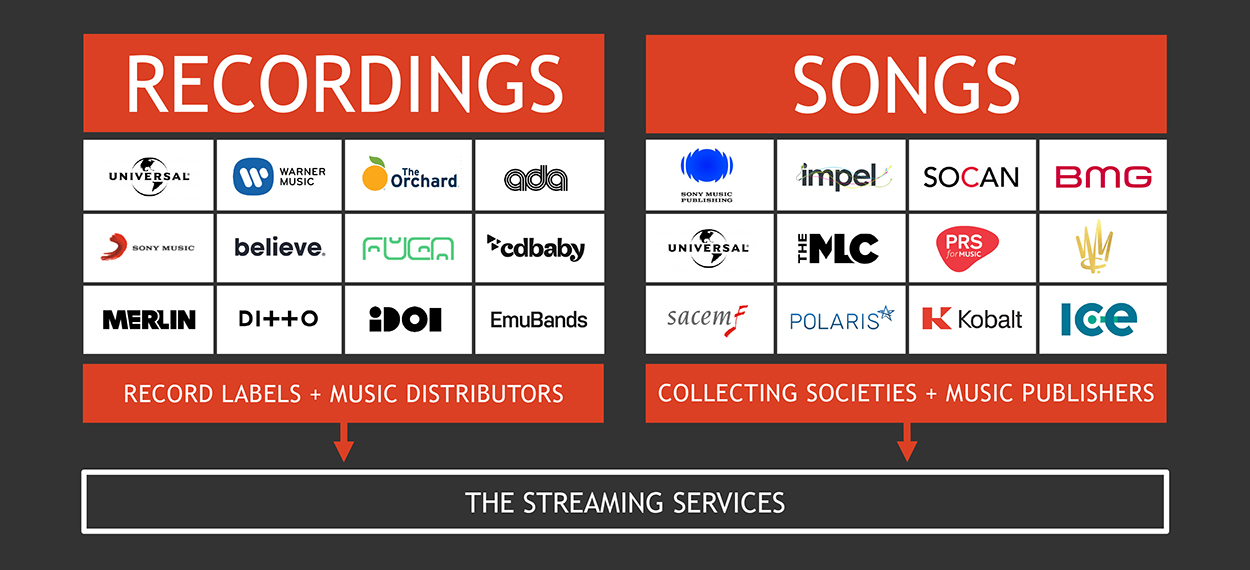

Digital platforms are usually making available recordings of songs.

In copyright terms, recordings and songs are two separate things. And as a result, different strands of the music industry manage recording rights and song rights – the record industry and the music publishing sector respectively.

This means that digital music platforms need to negotiate two sets of licensing deals – one set of deals covering recording rights with the record industry, and another set of deals covering song rights with the music publishing sector.

With recording rights, record labels and music distributors do the deals. Bigger labels – especially the three major record companies – will negotiate their own deals directly with each digital service. Many indie labels work with an organisation called Merlin which negotiates the deals.

Meanwhile other indies – as well as self-releasing artists – will rely on music distributors, which either negotiate their own deals or are also part of Merlin.

With song rights, some music publishers negotiate their own direct deals with the digital services for at least some of their repertoire. There’s also an organisation called IMPEL which negotiates deals for a group of smaller independent publishers.

But where publishers haven’t negotiated deals, the song right collecting societies will issue a licence instead, so in the UK that’s PRS and MCPS. Many collecting societies actually collaborate on digital licensing via so called licensing hubs, eg PRS and MCPS work with an organisation called ICE.

#03: The subscription streaming licensing model is revenue share based on consumption share.

Most subscription streaming services operate a revenue share based on consumption share business model.

It means that a service commits to share its revenues with the music industry every month, with what each licensing partner – ie label, distributor, publisher and society – receives based on what percentage of streams their music accounted for.

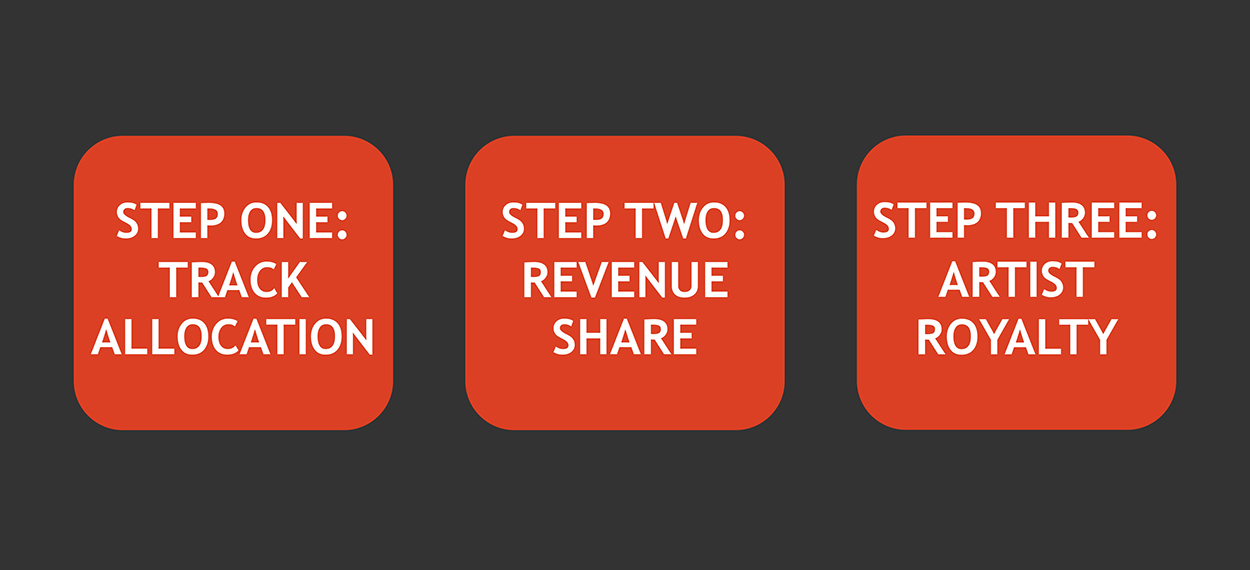

So, from an artist perspective, there is a three-step process to getting paid…

First, track allocation. Each track that has been streamed is allocated a share of that month’s total revenues based on what percentage of all the streams delivered it accounted for – ie if one track accounts for 0.01% of all streams, it will be allocated 0.01% of the money.

Second, revenue share. Whatever money has been allocated to a track is then shared with whichever label or distributor provided the recording, and whichever publisher or collecting society represents the song. Every deal is different, but usually 50-55% of the track allocation is paid to the label or distributor, while 10-15% is paid to the publisher or society.

Third, artist royalty. The label or distributor will share what it receives with the artist, and the publisher or society will share what it receives with the songwriter.

#04: What the artist earns depends entirely on their deals with their business partners.

What cut of the money the artist or songwriter receives depends entirely on their deals with whichever labels, distributors or publishers they are working with. Where a collecting society is involved, it depends on what fees the society charges as it processes the money.

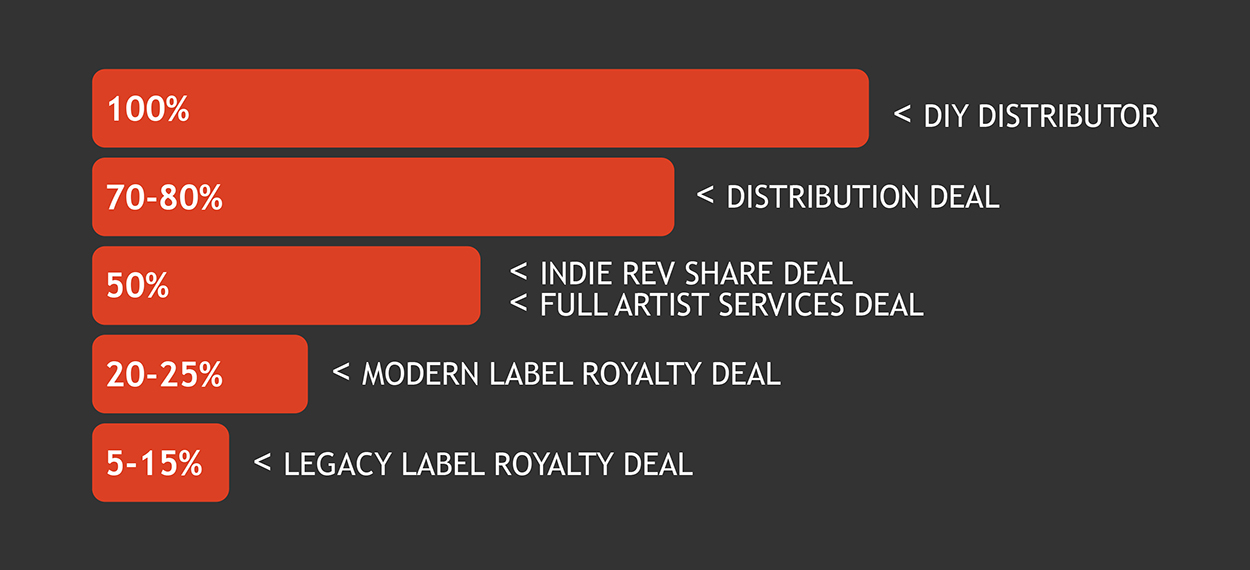

With recordings income, the artist’s cut could be anywhere from a few percent to 100% of the money, depending on their label or distribution deal.

How much the label or distributor keeps will depend on how much investment and how many services that label or distributor has provided. It may also depend on when the deal was done. Older record deals may well pay a lower cut of the money to the artist than newer record deals.

With new record deals in the UK, artists would usually receive at least 20% of any money allocated to their recordings, and some deals may be more like a 50/50 split. However, artists still locked into record deals that were negotiated before 2010 may get less than 20% – and the older the deal the lower their cut is likely to be.

Where an artist is basically running their own label and working with a distributor, they would usually get at least 50% of the money, and on a 50/50 deal they would usually have received a lot of extra services from the distributor. It’s more common in this scenario for the artist to get a majority of the money. With some DIY distributors, the artist pays an upfront distribution fee and gets 100% of the money.

It’s also important to note that labels, distributors and publishers may all advance money to music-makers when they first sign a deal, and that advance will be recouped out of future royalties. A label may also be able to recoup some of its other upfront costs from future income.

So, where a music-maker is ‘unrecouped’, they won’t necessarily get all or any of their cut of digital income paid into their bank accounts, because all or some of that money is paying off what is owed to the label, distributor or publisher.

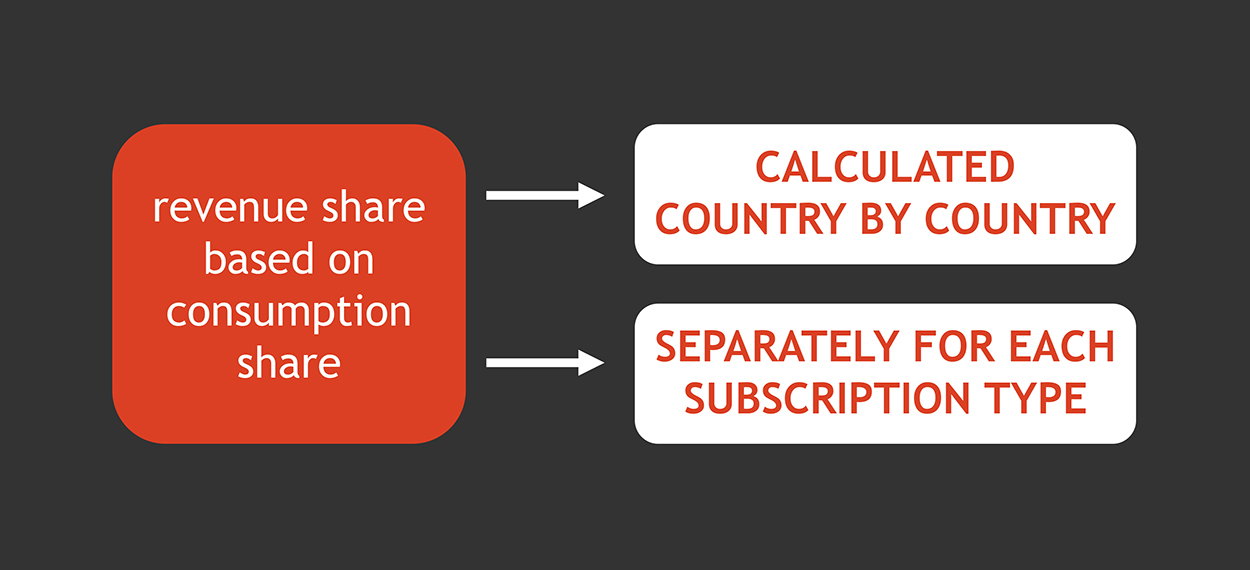

#05: Royalties are calculated separately by country and by subscription type.

It’s worth noting that the track allocation process described above is done separately for each country and each subscription type.

So premium subscription monies generated in the UK will be allocated to music streamed by a service’s premium subscribers in the UK; advertising monies generated in the UK will be allocated to music streamed by a service’s free subscribers in the UK; premium subscription monies generated in France will be allocated to music streamed by a service’s premium subscribers in France; and so on.

As a result, the average per-stream pay out in any one month will be different from country-to-country and depending on the subscription type.

Average pay-outs will always be higher on premium streams than free streams. And average pay-outs will be higher in more established music markets than newer music markets, because subscription fees are higher in the former than the latter.

It’s quite common to see lists doing the rounds on social media which seem to set out the per-stream pay-out for each streaming service.

However, it’s important to realise that any per-stream pay-outs stated on such lists are approximations, based on working out an average per-stream pay-out across an entire service.

And always remember: there are no fixed per-stream rates, and average per-stream pay-outs vary month-to-month, country-to-country, and depending on the kind of subscription.